In electronics, a current divider is a simple linear circuit that produces an output current (IX) that is a fraction of its input current (IT). Current division refers to the splitting of current between the branches of the divider. The currents in the various branches of such a circuit will always divide in such a way as to minimize the total energy expended. This can be shown by calculus.

The formula describing a current divider is similar in form to that for the voltage divider. However, the ratio describing current division places the impedance of the unconsidered branches in the numerator, unlike voltage division where the considered impedance is in the numerator. This is because in current dividers, total energy expended is minimized, resulting in currents that go through paths of least impedance, therefore the inverse relationship with impedance. On the other hand, voltage divider is used to satisfy kirchoff's voltage law. The voltage around a loop must sum up to zero, so the voltage drops must be divided evenly in a direct relationship with the impedance.

To be specific, if two or more impedance are in parallel, the current that enters the combination will be split between them in inverse proportion to their impedances (according to Ohm's law). It also follows that if the impedances have the same value the current is split equally.

Resistive divider

A general formula for the current IX in a resistor RX that is in parallel with a combination of other resistors of total resistance RT is (see Figure 1):

where IT is the total current entering the combined network of RX in parallel with RT. Notice that when RT is composed of a parallel combination of resistors, say R1, R2, ... etc., then the reciprocal of each resistor must be added to find the total resistance RT:

General case

Although the resistive divider is most common, the current divider may be made of frequency dependent impedances. In the general case the current IX is given by:

Using Admittance

Instead of using impedances, the current divider rule can be applied just like the voltage divider rule if admittance (the inverse of impedance) is used.

Take care to note that YTotal is a straightforward addition, not the sum of the inverses inverted (as you would do for a standard parallel resistive network). For Figure 1, the current IX would be

Example: RC combination

Figure 2 shows a simple current divider made up of a capacitor and a resistor. Using the formula above, the current in the resistor is given by:

-

where ZC = 1/(jωC) is the impedance of the capacitor.

The product τ = CR is known as the time constant of the circuit, and the frequency for which ωCR = 1 is called the corner frequency of the circuit. Because the capacitor has zero impedance at high frequencies and infinite impedance at low frequencies, the current in the resistor remains at its DC value IT for frequencies up to the corner frequency, whereupon it drops toward zero for higher frequencies as the capacitor effectively short-circuits the resistor. In other words, the current divider is a low pass filter for current in the resistor.

Loading effect

The gain of an amplifier generally depends on its source and load terminations. Current amplifiers and transconductance amplifiers are characterized by a short-circuit output condition, and current amplifiers and transresistance amplifiers are characterized using ideal infinite impedance current sources. When an amplifier is terminated by a finite, non-zero termination, and/or driven by a non-ideal source, the effective gain is reduced due to the loading effect at the output and/or the input, which can be understood in terms of current division.

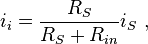

Figure 3 shows a current amplifier example. The amplifier (gray box) has input resistance Rin and output resistance Rout and an ideal current gain Ai. With an ideal current driver (infinite Norton resistance) all the source current iS becomes input current to the amplifier. However, for a Norton driver a current divider is formed at the input that reduces the input current to

which clearly is less than iS. Likewise, for a short circuit at the output, the amplifier delivers an output current io = Ai ii to the short-circuit. However, when the load is a non-zero resistor RL, the current delivered to the load is reduced by current division to the value:

Combining these results, the ideal current gain Ai realized with an ideal driver and a short-circuit load is reduced to the loaded gain Aloaded:

The resistor ratios in the above expression are called the loading factors. For more discussion of loading in other amplifier types, see loading effect.

Unilateral versus bilateral amplifiers

Figure 3 and the associated discussion refers to a unilateral amplifier. In a more general case where the amplifier is represented by a two port, the input resistance of the amplifier depends on its load, and the output resistance on the source impedance. The loading factors in these cases must employ the true amplifier impedances including these bilateral effects. For example, taking the unilateral current amplifier of Figure 3, the corresponding bilateral two-port network is shown in Figure 4 based upon h-parameters. Carrying out the analysis for this circuit, the current gain with feedback Afb is found to be

That is, the ideal current gain Ai is reduced not only by the loading factors, but due to the bilateral nature of the two-port by an additional factor ( 1 + β (RL / RS ) Aloaded ), which is typical of negative feed back amplifier circuits. The factor β (RL / RS ) is the current feedback provided by the voltage feedback source of voltage gain β V/V. For instance, for an ideal current source with RS = ∞ Ω, the voltage feedback has no influence, and for RL = 0 Ω, there is zero load voltage, again disabling the feedback.

Hi,

ReplyDeleteI had a question regarding the “Electronics Sites Links” page on your website. Are you accepting suggestions on this page?

If you are, I would like to suggest adding EE Power to the page. They are digital publication focused on the power electronics industry. The publication features technical articles, design tips, and application notes from the industry’s leading power electronics engineers and application experts. Here is the URL for the site if you’d like to check it out:

https://eepower.com/

Let me know what you think of this suggestion or if you need any additional information!

Best,

Marge

Hi,

ReplyDeleteI was wondering what your thoughts were on “EE Power”, would you consider adding them to the “Electronics Sites Links” page? Here is the URL for their website if you would like to have a look:

https://eepower.com/

I am looking forward to hear from you the soonest.

Best,

Marge